Whales - Up Close

Excerpt from our chapter: Cheated

Reproduction

The reproduction of marine mammals is not only extremely complicated but must also be successful every time because sperm whales can usually only give birth to a new calf every four to six years.

Fin whale or blue whale

The whalers immediately began cutting up the whale, but Klaus Barthelmess took another closer look at the whale and discovered some discrepancies. The back was gray-black and had the typical color of a fin whale, the underside of the flippers were white as was the entire belly. However, near the navel, some white pigment spots were visible on a light gray background. However, this is typical of a blue whale, which has exactly these pigment spots all over its body. The whale's entire color pattern has been described as symmetrical and uniform, but this is not the case with the fin whale because its typical identifying feature is its asymmetrical color pattern on its head, which continues down to the baleen. The right side as well as the oral cavity and baleen plates are creamy white, while the left side is uniformly gray.

The overall shape of the head, however, was clearly that of a fin whale, namely pointed and slender, more V-shaped rather than wide and flat and U-shaped like that of a blue whale. However, most of the whale's baleen was solidly black, which is again true for a blue whale.

However, the baleen plates were far too thin and fine for a blue whale and when they were removed, some of the baleen were still lighter in color.

So it was a fin whale after all?

The shape and size of the dorsal fin also caused headaches. It had features of the dorsal fin of a blue whale, but at 53 cm it was significantly larger than previously measured sizes of 40 cm.

Fin whales can reach a dorsal fin of usually up to 64 cm, although their crescent-shaped, slightly backward-sloping shape differs significantly from that of blue whales.

The hybrid whale

Barthelmess slowly developed the theory that this was neither a fin whale nor a blue whale, but rather a cross between the two types of whale. Despite the late hour, Barthelmess drummed the other scientists out of bed and tissue samples were taken. What later turned out to be very important, because these samples could later be used to discover important details about this extraordinary animal with the help of DNA analysis.

After initial external examinations by Klaus Barthelmess and the other scientists, we were actually already sure. This whale killed (No. 5 of the 1986 whaling season) was a hybrid whale, or as the old whalers used to say: a bastard.

As the whale was further processed, the uterus and ovaries were also routinely examined. The sensational discovery was made that the whale was pregnant, although hybrids are normally not considered capable of reproduction.

The fetus, which was approximately 20 cm in size, was recovered and was also genetically examined. In 1991, the scientific evaluation and publication of the research results of researcher R. Spilliart and his colleagues from the Marine Research Institute in Reykjavik, Iceland, for this hybrid whale appeared for the first time.

It was confirmed that this female animal, aged 7 years, was a cross between a female blue whale and a male fin whale. Analyzes of the unborn calf showed that the hybrid animal had mated with a male blue whale.

The ovaries

People were all the more astonished when the ovaries of this hybrid whale were examined and signs of old and scarred tissue were found in one ovary, which is called corpus albicans and could indicate a previous pregnancy. During the ovulation of an egg, the follicle from which the egg emerged fills with yellow tissue and the corpus luteum is formed, also called the corpus luteum (Latin corpus “body” and luteus “yellow”). This corpus luteum has the function of producing the hormones estrogen and progesterone, which ensure the maintenance of pregnancy. In the first 7-8 weeks of pregnancy, progesterone is produced almost exclusively by the corpus luteum, after which this task is predominantly taken over by the placenta. Only after birth does this shrink into a narrower, tough tissue and then consists exclusively of connective tissue, which appears white due to cicatricial transformation and is therefore given the name white body, Corpus albicans (Latin albicare "white").

If pregnancy does not occur, the corpus luteum in the ovary perishes more quickly. The large number of converted corpus luteums into corpus albicans then give the aging ovary its scarred appearance. This procedure can also be observed in human ovaries, because this scarred connective tissue can also be seen in the shrunken ovaries of menopausal women.

From the Handbook of Northern European Sea Fisheries, Volume XI Issue 6, from 1955, we also found an interesting reference from the earlier whaling era, because the old whalers determined the age and sexual maturity of the whales based on their ovaries, among other things. Even an external inspection of the ovaries, their size, weight and the maturing follicles indicated sexual maturity to the ancient whalers.

They also drew conclusions about the age of the whales based on the number of Corpora albicantia. At a time when whaling was active, whalers naturally had sufficient material to examine the animals they killed. Organs and intestines could be measured and weighed and so the authors of this book report that the ovaries of sexually mature whales can be up to 40 cm long, in contrast to younger, immature animals whose ovaries are only the size of a hand.

The size of an egg cell has been reported to be an average of 4.5 - 5.4 mm, while the human egg cell is only 0.11 - 0.14 mm in size and is just visible to the naked eye. The weight of the ovaries in some whales was 258 grams, while human ovaries weigh just 10-14 grams. And although this weight and length seem huge to us, they are not disproportionate in relation to the total length when compared in size to the human ovaries of a sexually mature woman, whose length is approximately 2.5 to 5 cm.

The corpus luteum

However, the information about the size and weight of the corpus luteum found in pregnant females is impressive. The blue whales were 10 centimeters tall and 1.5 to 12 kg, while the fin whale weighed 1 to 10 kg and the sperm whale 0.3 to 1.2 kg, just a single corpus luteum. The hormone from these corpus luteums, progesterone, was also used and preserved by freezing or made durable with formalin. And the yield of these effective hormones was considerable, because the same amount of hormones could be obtained from the corpus luteum of a single whale as from the corpus luteum of about a thousand pigs.

Hybrid baleen whales:

Surprisingly, there are already references to hybrid whales in the records of ancient whalers. In 1887 A.H. reported Cocks already from 6 hybrid whales along the coast of Lapland. But it wasn't until a century later that the first scientifically documented case using molecular analysis emerged. In 1970, researcher Doroshenko reported a hybrid between a blue and fin whale that was caught off Kodiak Island in the Gulf of Alaska in 1965.

There are now a total of 11 confirmed baleen whale hybrids from the wild, captured exclusively during the active whaling season. In all cases these were always crosses between blue and fin whales.

3 hybrids, one female and two males, were captured between 1983 and 1989 during the Icelandic whaling season. The most sensational case is certainly the hybrid discovered by Klaus Barthelmess, which was later described in detail by Spillart.

Hybrid toothed whales

The reason for these crosses in the wild is certainly the close social coexistence of dolphins with one another. Sexual play, touching and intercourse are a big part of it for dolphins.

Off the Bahamas, underwater cameras were used to observe spotted dolphins and bottlenose dolphins living together in a large school. Almost 50% of male bottlenose dolphins were the initiators of sexual contacts with spotted dolphins.

As the number of dolphins in captivity has increased, the number of hybrids has also increased and is therefore an interference by us humans. One result of this reports an extraordinary crossbreeding of a bottlenose dolphin and a Guiana dolphin, which never live together in the wild. The Guiana dolphins live exclusively in bays, shallow waters and even estuaries on the western Atlantic coast of South and Central America. A female hybrid dolphin named Luna was born in the Islas del Rosario aquarium in Colombia in May 1996, but unfortunately died in October 2002. The parents were a male Guiana dolphin and a female bottlenose dolphin.

Hybrid whale and dolphin

The most spectacular case is certainly the “Wholphin”. The name is a combination of the English words whale and dolphin. This wholphin is a rare cross between a killer whale and a dolphin - the bottlenose dolphin. Although these two types of animals are different species, scientists consider them to be in the same subfamily.

The first captive-born wolf was born on May 15, 1985 at the Sea Life Aquarium in Hawaii. The parents were a female dolphin named Punahele and a male killer whale named Tanui Hahai. The baby was named Kekaimalu, was female and was the star of the aquarium. In June 1990 she caused a stir because she gave birth to her first baby at the age of 5. However, it died after just a few days because Kekaimalu was actually far too young to give birth to its own offspring.

A year later in November 1991 she gave birth to a daughter named Pohaikealha, who survived the first few years well but then died at the age of 9. On December 23, 2004, at the age of 19, Kekaimalu had her third daughter named Kawili Kai, who was fathered by a male bottlenose dolphin and therefore has three-quarters of the genetic makeup of a bottlenose dolphin.

Even different species of porpoises, such as the common porpoise and the white-flanked porpoise, mate with each other, and in 1990 a skeleton of a hybrid whale that came from a narwhal and a beluga was even found in Disko Bay in West Greenland.

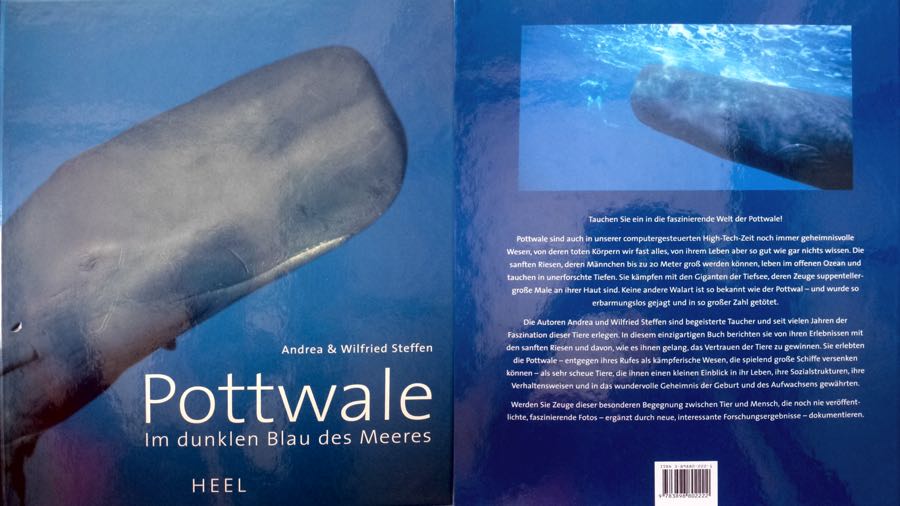

Die Autoren Andrea und Wilfried Steffen sind begeisterte Taucher und seit vielen Jahren der Faszination dieser Tiere erlegen. In diesem einzigartigen Buch berichten sie von Ihren Erlebnissen mit den sanften Riesen und davon, wie es ihnen gelang, das Vertrauen der Tiere zu gewinnen. Sie erlebten die Pottwale – entgegen ihres Rufes als kämpferische Wesen, die spielend große Schiffe versenken können- als scheue Tiere, die ihnen einen kleinen Einblick in ihr Leben, ihre Sozialstrukturen, ihre Verhaltensweisen und in das wundervolle Geheimnis der Geburt und des Aufwachsen gewährten.

Die Autoren Andrea und Wilfried Steffen sind begeisterte Taucher und seit vielen Jahren der Faszination dieser Tiere erlegen. In diesem einzigartigen Buch berichten sie von Ihren Erlebnissen mit den sanften Riesen und davon, wie es ihnen gelang, das Vertrauen der Tiere zu gewinnen. Sie erlebten die Pottwale – entgegen ihres Rufes als kämpferische Wesen, die spielend große Schiffe versenken können- als scheue Tiere, die ihnen einen kleinen Einblick in ihr Leben, ihre Sozialstrukturen, ihre Verhaltensweisen und in das wundervolle Geheimnis der Geburt und des Aufwachsen gewährten.

Werden Sie Zeuge dieser besonderen Begegnung zwischen Tier und Mensch, dokumentiert mit noch nie veröffentlichten, faszinierenden Fotos und ergänzt durch neue, interessante Forschungsergebnisse.

Werden Sie Zeuge dieser besonderen Begegnung zwischen Tier und Mensch, dokumentiert mit noch nie veröffentlichten, faszinierenden Fotos und ergänzt durch neue, interessante Forschungsergebnisse.

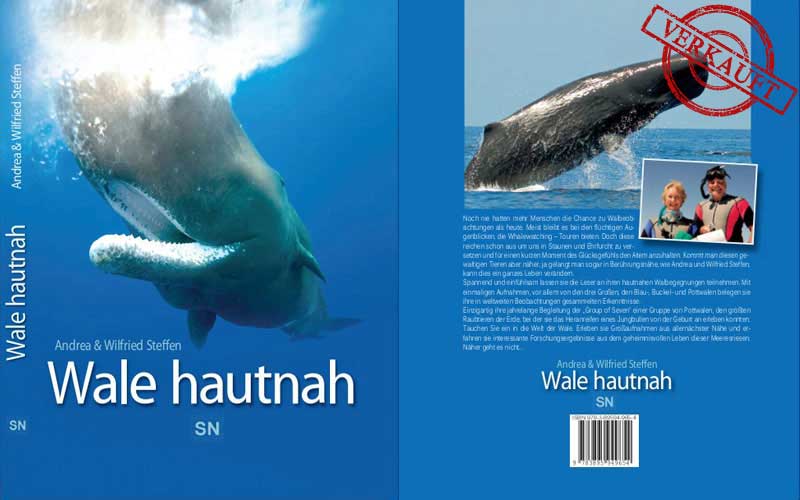

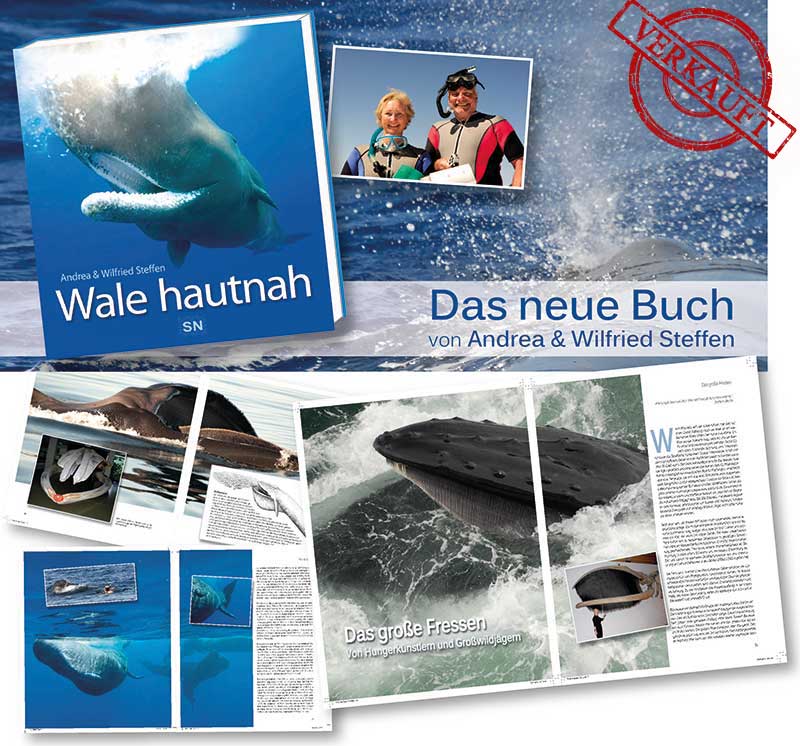

Spannend und einfühlsam lassen sie die Leser an ihren hautnahen Walbegegnungen teilnehmen. Mit einmaligen Aufnahmen, vor allem von den drei Großen: den Blau-, Buckel- und Pottwalen, belegen sie ihre in weltweiten Beobachtungen gesammelten Erkenntnisse. Einzigartig ihre jahrelange Begleitung der „Group of Seven“, einer Gruppe von Pottwalen, den größten Raubtieren der Erde, bei der sie das Heranreifen eines Jungbullen von der Geburt an erleben konnten.

Spannend und einfühlsam lassen sie die Leser an ihren hautnahen Walbegegnungen teilnehmen. Mit einmaligen Aufnahmen, vor allem von den drei Großen: den Blau-, Buckel- und Pottwalen, belegen sie ihre in weltweiten Beobachtungen gesammelten Erkenntnisse. Einzigartig ihre jahrelange Begleitung der „Group of Seven“, einer Gruppe von Pottwalen, den größten Raubtieren der Erde, bei der sie das Heranreifen eines Jungbullen von der Geburt an erleben konnten.

Tauchen Sie ein in die Welt der Wale. Erleben sie Großaufnahmen aus allernächster Nähe und erfahren sie interessante Forschungsergebnisse aus dem geheimnisvollen Leben dieser Meeresriesen.

Tauchen Sie ein in die Welt der Wale. Erleben sie Großaufnahmen aus allernächster Nähe und erfahren sie interessante Forschungsergebnisse aus dem geheimnisvollen Leben dieser Meeresriesen.