Sperm whales – in the dark blue of the sea

Excerpt from our chapter: Close up

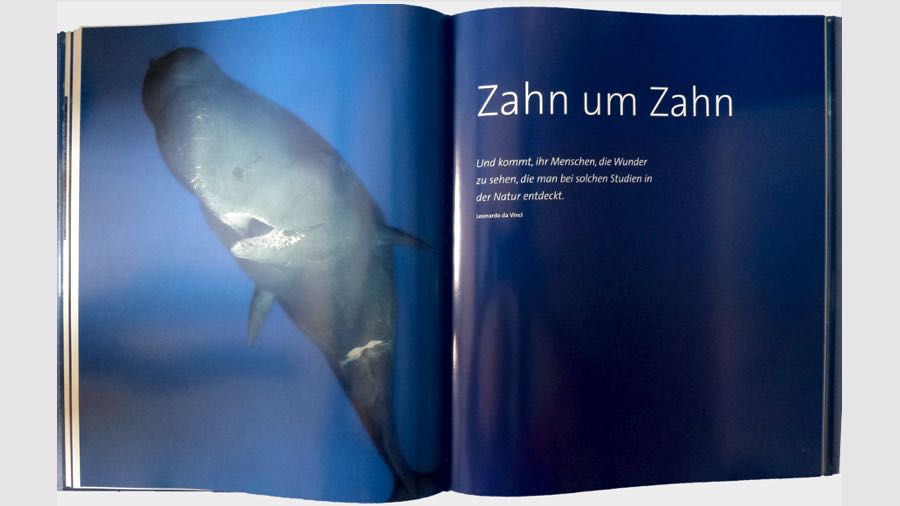

The Skin

Just like humans, the miracle skin is a true multi-talent. It protects, tempers, regulates and feels.

In humans, the dark skin pigment melanin, which we need to protect against sunburn, is found in the extremely thin epidermis, which is on average only a tenth of a millimeter thick. In our underlying leather skin (dermis) we perceive the sensations of pain, pressure, cold and heat. In addition to the many nerve endings, there are also blood vessels, sebaceous glands and around three million sweat glands that ensure the body maintains the correct body temperature.

The subcutaneous fatty tissue underneath our dermis cushions the body and forms fat stores for times of need. The structure of our human skin can be largely compared to that of whale skin, but with one very big exception. We humans have sweat glands in our skin, which a whale obviously doesn't have because its skin has to be absolutely waterproof.

Nature has also performed a miracle with whale skin, because this skin had to be specially adapted to life in water.

Like humans, whale skin consists of epidermis, dermis and fat pads.

The whale's dermis is, despite its fat cells, very thin and wide-meshed. For this reason, whale skin can never be tanned. Only the leather skin on the fins and flukes is more stable and therefore more resilient.

Like the epidermis, the dermis is permeated by many nerve endings and thin blood vessels. However, it does not contain any color bodies, which makes it appear colorless and it merges invisibly into the blubber layer (bubble).

This thick layer of blubber, which can be 5 - 50 cm thick, serves on the one hand to regulate body temperature and on the other hand as a fat reserve that a whale has to live on in times of hunger.

The Temperature

Whales are warm-blooded animals and, like us humans, must always keep their body temperature at around 36 degree C, which is very complicated due to their extensive activities.

The water temperature can be up to 30 degree C in the tropics. Here the whale has to contend with excess heat, which is exacerbated by swimming, jumping or mating activities. When it dives down to look for food, it reaches depths where the water temperature is only 2 degree C. Since he can stay here for half an hour or longer, a lot of heat is removed from the body.

If he is in arctic waters, there is a significant loss of heat just by breathing. Whales cannot curl up in the cold to retain heat, nor can they sweat to release excess heat because they lack sweat glands. To compensate for all this, the whale has developed several ways to prevent overheating or hypothermia.

One way to generate heat is to process food. A chemical process takes place during digestion. The food is broken down into its components and heat is released. Fish, which contain a lot of protein, give off 40% more heat than fats and carbohydrates. The sperm whale, which feeds primarily on fish and squid, can use this heat from proteins to maintain its body temperature in colder waters. Migrant male sperm whales may also stop feeding when they reach warmer waters because they need to process and release excess caloric heat in the tropics. During their migrations they feed on their stored fat. By combining feeding in the polar seas and fasting in the tropics, they can regulate their temperature very effectively.

In this type of heat regulation, body size is also of crucial importance, because an animal's body heat also has a certain relationship to body size. The smaller the size of an animal, the greater the need for heat. The larger the body, the lower the need for metabolic heat per kilogram. The best example here is the shrew and the elephant. The tiny shrew burns energy so quickly that it has to eat twice its body weight every day, while the elephant's combustion process is very slow and therefore only needs 4% of its body weight in food every day. Our even larger sperm whales only consume 3% of their body weight in food.

However, heat regulation through the bloodstream is more effective than heat generation through food. The thick layer of blubber that insulates the muscles and internal organs is permeated with many blood vessels. By narrowing or widening the blood vessels, the whale can control blood circulation.

The heat in the arteries is transferred by circulation to the external veins in the fins that are not covered with the insulated blubber layer, thereby cooling. The cool blood flowing back from the fins is warmed in contact with fresh arterial blood, creating heat exchange.

In large whale species, body temperature regulation is somewhat more difficult than in smaller species or dolphins because the blubber layer increases in proportion to the animal's body length. Since whales can grow up to ten times longer than dolphins, their blubber layer also becomes ten times thicker and their thermal insulation increases accordingly. This puts them at an advantage when it comes to maintaining body temperature, but at a disadvantage when it comes to cooling down. Smaller species and dolphins with a thinner blubber layer can get rid of excess heat much better.

The whales or dolphins cannot “sweat out” their excess heat because their skin must be absolutely waterproof. She is perfectly adapted to her life element. The skin must protect the whale from being softened by the salt water and from losing its own body fluids. This is also the reason why they do not have open pores in the skin through which water exchange takes place. But when the whales leave their water element, for example when they strand, their skin is mercilessly exposed to the sun. It dries out quickly, becomes cracked and burns immediately. The whales get sunburned. This is also the reason why you always have to spray live stranded animals with water or cover them with damp cloths.

The Color

The color of the whales can also vary considerably depending on their age. The white color, for example in beluga whales, indicates the final stage of growth and skin development.

The young animal, on the other hand, has a very dark color and goes through several intermediate stages before it turns white as it grows older. But there are other species that also change their color as they age.

In the case of spotted dolphins, the young animals do not show any spots at birth and the different pigmented spots only become visible as they grow.

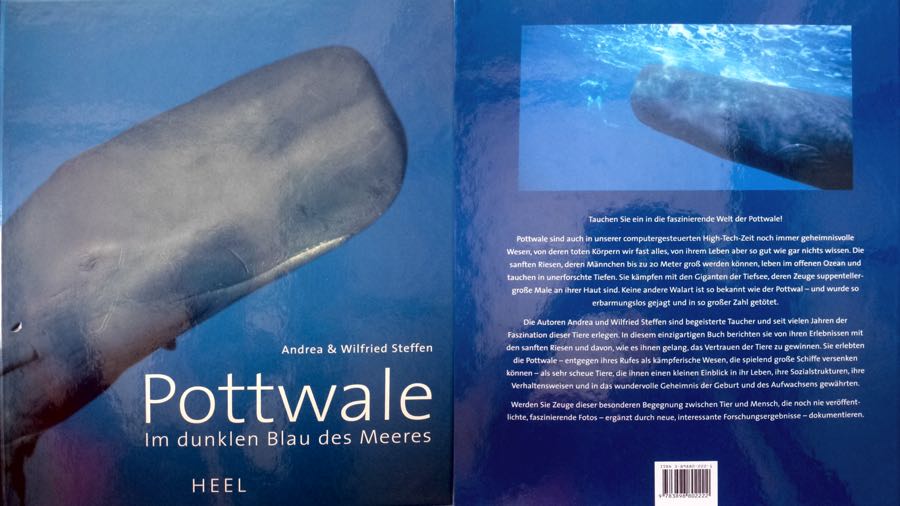

Die Autoren Andrea und Wilfried Steffen sind begeisterte Taucher und seit vielen Jahren der Faszination dieser Tiere erlegen. In diesem einzigartigen Buch berichten sie von Ihren Erlebnissen mit den sanften Riesen und davon, wie es ihnen gelang, das Vertrauen der Tiere zu gewinnen. Sie erlebten die Pottwale – entgegen ihres Rufes als kämpferische Wesen, die spielend große Schiffe versenken können- als scheue Tiere, die ihnen einen kleinen Einblick in ihr Leben, ihre Sozialstrukturen, ihre Verhaltensweisen und in das wundervolle Geheimnis der Geburt und des Aufwachsen gewährten.

Die Autoren Andrea und Wilfried Steffen sind begeisterte Taucher und seit vielen Jahren der Faszination dieser Tiere erlegen. In diesem einzigartigen Buch berichten sie von Ihren Erlebnissen mit den sanften Riesen und davon, wie es ihnen gelang, das Vertrauen der Tiere zu gewinnen. Sie erlebten die Pottwale – entgegen ihres Rufes als kämpferische Wesen, die spielend große Schiffe versenken können- als scheue Tiere, die ihnen einen kleinen Einblick in ihr Leben, ihre Sozialstrukturen, ihre Verhaltensweisen und in das wundervolle Geheimnis der Geburt und des Aufwachsen gewährten.

Werden Sie Zeuge dieser besonderen Begegnung zwischen Tier und Mensch, dokumentiert mit noch nie veröffentlichten, faszinierenden Fotos und ergänzt durch neue, interessante Forschungsergebnisse.

Werden Sie Zeuge dieser besonderen Begegnung zwischen Tier und Mensch, dokumentiert mit noch nie veröffentlichten, faszinierenden Fotos und ergänzt durch neue, interessante Forschungsergebnisse.

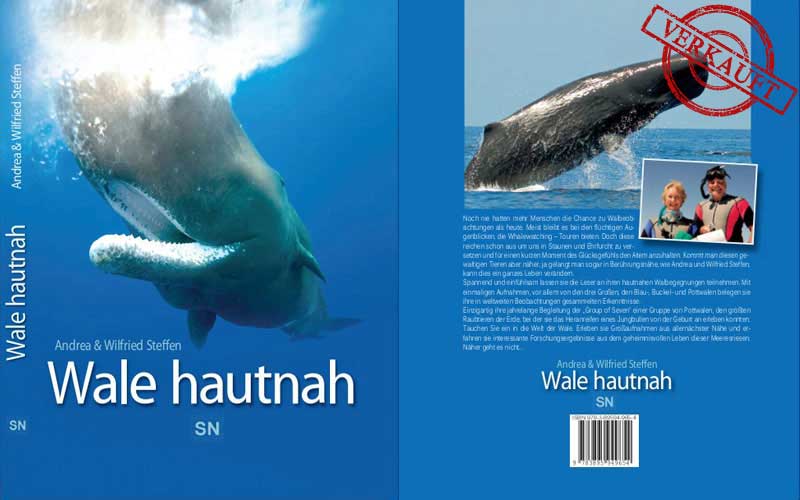

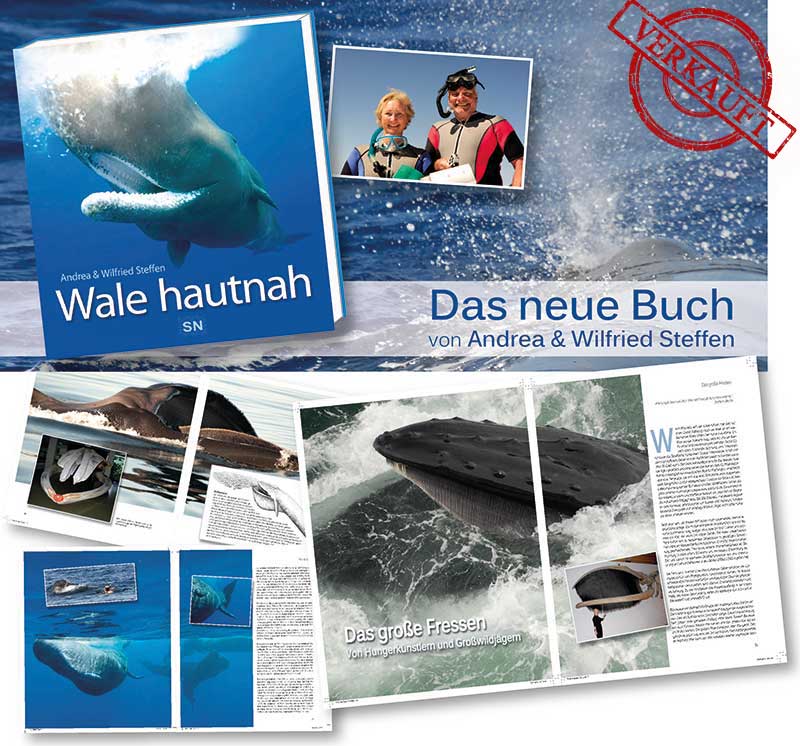

Spannend und einfühlsam lassen sie die Leser an ihren hautnahen Walbegegnungen teilnehmen. Mit einmaligen Aufnahmen, vor allem von den drei Großen: den Blau-, Buckel- und Pottwalen, belegen sie ihre in weltweiten Beobachtungen gesammelten Erkenntnisse. Einzigartig ihre jahrelange Begleitung der „Group of Seven“, einer Gruppe von Pottwalen, den größten Raubtieren der Erde, bei der sie das Heranreifen eines Jungbullen von der Geburt an erleben konnten.

Spannend und einfühlsam lassen sie die Leser an ihren hautnahen Walbegegnungen teilnehmen. Mit einmaligen Aufnahmen, vor allem von den drei Großen: den Blau-, Buckel- und Pottwalen, belegen sie ihre in weltweiten Beobachtungen gesammelten Erkenntnisse. Einzigartig ihre jahrelange Begleitung der „Group of Seven“, einer Gruppe von Pottwalen, den größten Raubtieren der Erde, bei der sie das Heranreifen eines Jungbullen von der Geburt an erleben konnten.

Tauchen Sie ein in die Welt der Wale. Erleben sie Großaufnahmen aus allernächster Nähe und erfahren sie interessante Forschungsergebnisse aus dem geheimnisvollen Leben dieser Meeresriesen.

Tauchen Sie ein in die Welt der Wale. Erleben sie Großaufnahmen aus allernächster Nähe und erfahren sie interessante Forschungsergebnisse aus dem geheimnisvollen Leben dieser Meeresriesen.